»The Housewife Should Not Overload the Table.” Scenes from the Life of Sister Felicita Kalinšek

Terezija Kalinšek was born on September 5, 1865, in Podgorje near Kamnik to her father Tomaž Kalinšek and mother Uršula. In 1892, she entered the novitiate of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in Maribor, where she received the religious name Felicita. She took her perpetual vows in 1896. She trained as a teacher and took over the management of the convent kitchen.

In 1898, an Agricultural and Culinary School was established in Ljubljana, and the 33-year-old Sister Felicita was appointed as a cooking teacher. Her reputation grew rapidly—she was entrusted with the cooking for the bishop, and she also taught girls from wealthy bourgeois families the importance of domestic skills, then considered “a most important duty in every household.” The kitchen was always lively and cheerful; the students adored her, and she gave herself fully to her vocation.

Soon after arriving in Ljubljana, she was asked to prepare a new edition of Slovenska kuharica (The Slovenian Cookbook) by Magdalena Pleiweis, originally published in 1868 as the first Slovenian cookbook written in the native language. Before that, Slovenians had only Vodnik’s Cookery Book, but Valentin Vodnik—although a skilled translator from german language—was no cook. Felicita took on the task with great diligence and responsibility, noting that “not every girl is fortunate enough to have wealthy parents; therefore, we must find other ways to educate those less privileged in this important field.”

Soon after arriving in Ljubljana, she was asked to prepare a new edition of Slovenska kuharica (The Slovenian Cookbook) by Magdalena Pleiweis, originally published in 1868 as the first Slovenian cookbook written in the native language. Before that, Slovenians had only Vodnik’s Cookery Book, but Valentin Vodnik—although a skilled translator from german language—was no cook. Felicita took on the task with great diligence and responsibility, noting that “not every girl is fortunate enough to have wealthy parents; therefore, we must find other ways to educate those less privileged in this important field.”

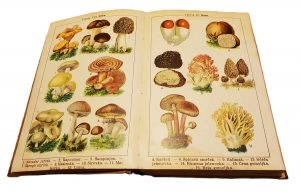

She revised and expanded the manual. In the sixth edition (1912), her name appeared for the first time. Later, she more than doubled the number of recipes, added new chapters, included a glossary of culinary terms, and eliminated outdated units of measurement. Her guiding principles were seasonality and locality. She introduced many new ingredients and modern techniques for preserving food, ensuring that housewives could still cook confidently in winter when fresh produce was scarce—and also improve their annual income. The eighth edition (1935), published entirely under her name, was renamed The Great Slovenian Cookbook (Velika slovenska kuharica).

“As people progress in all areas of life, so too must cooking progress,” she wrote. Today, Sister Felicita Kalinšek is best known as the author of this iconic Slovenian cookbook, which—with its numerous editions and adaptations—has remained in print to this day. It is recognized as the cookbook with the longest publication tradition in Europe. But The Slovenian Cookbook is more than just a collection of recipes and precise household instructions—it is a valuable document of the time, place, and values of the era in which Felicita lived and worked.

numerous editions and adaptations—has remained in print to this day. It is recognized as the cookbook with the longest publication tradition in Europe. But The Slovenian Cookbook is more than just a collection of recipes and precise household instructions—it is a valuable document of the time, place, and values of the era in which Felicita lived and worked.

At the turn of the 20th century, women’s roles in society were still clearly defined. Education was aimed at preparing them for their “profession” as good wives, mothers, and above all, skilled homemakers. Within this context, Felicita Kalinšek served as a teacher, educator, author, and one of the first to lay professional foundations in the field of domestic economy.

To fully understand the significance of her work, we must look closely at the time in which she lived. Doing so allows us to see Sister Felicita not merely as the author of a beloved cookbook, but as an important chronicler of her era, whose knowledge and dedication contributed to Slovenia’s cultural heritage. In this light, the words of the devoted nun take on a whole new meaning.